Seattleite’s have experienced a rapid rise in housing cost over the past six years. Hundreds of people move here every day, with only half the number of homes built that are needed to accommodate them. Still, immense physical change has happened in many of our local neighborhoods. As more folks are displaced to southern suburbs and the streets themselves, the loss of community has run toe-to-toe with places of memory being written over with new construction. The number of houseless people in the county has doubled to over 11,000 in just a few years, each 5% bump in rent putting over 200 families in the cold, killing 69 people last year alone. People see no hope for the future or the life that $75,000 houses gave their parents. Seattle is among Vancouver, San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, London, and dozens of other cities globally in this deadly crisis.

In cities across North America, the anti-capitalist left has become bitterly divided on how to go about solving this pressing civic issue, both sides recognizing the financial investment root. One faction gets characterized as ‘NIMBYs’ to varying fairness: neighborhood groups, former candidate Jon Grant, John Fox’sSeattle Displacement Coalition, the blog Outside City Hall, Seattle Fair Growth, and popular social media diary Vanishing Seattle.

NIMBY is a term historically used to describe white wealthy suburbanites that respond to desegregation, shelters, low income housing, and public transportation with “Not in my backyard!” on the basis of “neighborhood character” or enshrined private property rights that to them must include ostensibly freezing one’s surroundings in amber. Pat Murakami, the Seattle Times Editorial Board’s endorsed council candidate this past election, is a perfect example of someone with a NIMBY point of view, absolutely separate from the Jon Grant camp. Journalist Erica Barnett writes:

Murakami opposed efforts to locate Casa Latina, the day-labor center that serves primarily Spanish-speaking immigrant workers, to a site on Rainier Avenue; unsuccessfully fought El Centro De La Raza’s plans to provide services and affordable housing at the Beacon Hill light rail station; and led efforts to prevent transit-oriented development out of the Rainier Valley. In its endorsement, the Times editorial board wrote that Murakami would ‘broaden the council’s representation and strengthen the voice of residents who own homes’

Urbanists that self-identify with “Yes In My Backyard” make up the opposing faction. The group gets dismissed as ‘shilling for corporate developers’ with ideas to only increase gentrification and displacement. Concentrated protests targeting YIMBYs in San Francisco have drawn personal threats of violence. Escalation in Seattle is more limited to throws of “brocialist” or “broburnist,”-‘splaining, sometimes as self-criticism within the same side. However, the divide made for a very ugly campaign between two people that both want radical change and affordability for the working class. Labor and health care activist Teresa Mosqueda ultimately won against Tenant’s Union alumni and frontline action frequenter Jon Grant. When Mosqueda’s campaign received a $250 donation from Maria Barriento, who owns a development firm of both low income and market rate projects, Grant supporters characterized Mosqueda as controlled by developer money.

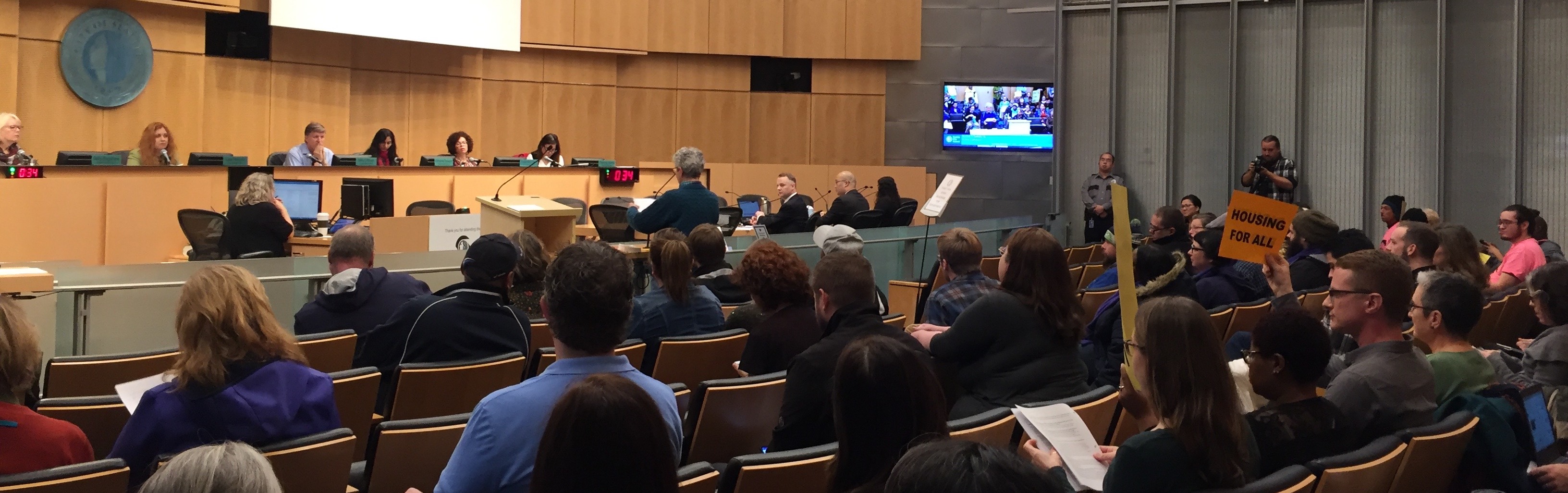

There are genuine people with genuine care for unhoused and marginalized communities of both the growth-skeptic and YIMBY persuasions, as well as unnecessarily combative and insensitive attitudes. We all need to do better to live up to the shared value of housing as a human right, and figure out what’s going to work in the shortest term possible. Thankfully, there’s a campaign that could potentially do it, the new coalition, Housing For All. The coalition intensely organized on the immediate 2018 budget goals of stopping the sweeps and passing a $100/employee tax on corporations to fund housing.

It’s important to know the historical context of the zoning that folks are fighting over.

In the Industrial era of the late 19th century, cities were coal-powered and unhygienic. Only the factory-owning Bourgeoisie could afford the private transportation and land to escape the city, making that lifestyle tantalizing to a middle class that would soon develop.

The first wave of white flight away from inner-city neighborhoods like Pioneer Square (where the term “skid row” originated) occurred as real estate-backed streetcar lines allowed the U-District, Wallingford, West Seattle, Queen Anne, and Columbia City to support commuters. Zoning in Seattle was established in 1923, seven years after New York City pioneered the practice. The regulation kept industrial uses away from these neighborhoods, concentrated along the undesirable central neighborhoods. The environmental health effects of pollution are still prominent today: with contaminated soil and high rates of asthma, the life expectancy in the industrial-enclosed, and mostly POC-inhabited South Park is 8 years lower than Seattle’s average.

Zoning regulations formed the neighborhoods homogenous, of residential, single family use only. Apartments, duplexes, and in-house corner stores were banished, and over time the amount of land needed for one house to be permitted has grown to between 5,000 and 9,600sqft – double to quadruple what most of the early 1900s Craftsman bungalows that blanket Seattle have. This means the rare areas that haven’t yet been developed are built up for far richer and fewer families than most neighborhoods in the city already look like – such as a cul-de-sac of large houses under construction right by the 120 rapid bus line and future Link station in the diverse and mixed-income Delridge District.

Through the 1950s, builders of the new neighborhoods put racially restrictive covenants in the deeds,punishing realtors with disbarment for selling homes to people of color. Neighborhood associations formed to lobby expanding and maintaining policies like these to keep low income and people of color out. The justifications for such segregation frequently cited one’s Constitutional right to “Freedom of Association,” as well as concerns of maintaining property values.

The central residential neighborhoods, deemed unappealing, were the only neighborhoods Seattle’s growing black and immigrant populations were allowed to live in. The Federal Housing Authority deemed the Central area a hazardous loan risk, meaning black Americans were not able to get mortgages on houses in Seattle, having to pay in full cash up front, or more often rent from exploitative landlords.The Color of Lawby Richard Rochstein cites the autobiography of Langston Hughes, where he, “described how, when his family lived in Cleveland in the 1910s, landlords could get as much as three times the rent from African Americans that they could get from whites, because so few homes were available to black families outside a few integrated urban neighborhoods. Landlords, Hughes remembered, subdivided apartments designed for a single family into five or six units, and still African Americans’ incomes had to be disproportionately devoted to rent.” Evicted, a recent book by Matthew Desmond set in Milwaukie, notes how this expensive ‘slum’ trend continues today in the form of the few landlords that serve people with criminal records, this population constituting a third of black Americans thanks to systemic racism in the criminal justice system. With rent inflated and mortgages unavailable to people of color, the homeownership that passes wealth through generations of families and creates a safety net remains exclusionary.

The post-war era of white flight led growth of the middle class out of city limits across the country, intending to diminish class consciousness by guaranteeing every white family could achieve homeowner status, subsidized with Veteran’s Affairs loans and freeway construction. It turned the white working class into a petite bourgeois that has interest in the market always rising, and competes against others to secure their retirement fund—not wanting to be an elderly person facing houselessness. Population decline, and thus tax base loss, then caused the collapse of public services such as public transit, parks, and school systems. Suburban dwellers still dependent on the city, but not taxed by it, were able to fund economically segregated luxury services. Freeway construction to transport suburbanites tore through communities of color, offering unjust compensation. These policies allowed white families to gain generational equity as property values rose while excluding people of color, painting the world of today where average black families have 1/13th the net wealth of white ones.

Adaptations for affordability found in places like the Central District were the exact opposite of the trend in zoning laws, pushing garage corner stores that allowed self-employment from home, and Mansions-turned-triplexes. This mixed-use, walkable community is exactly what is now attractive to young middle class white people, branded “The Creative Class” by Richard Florida, who now writes about the gentrifying aftermath as “The New Urban Crisis.”

Today, two thirds of Seattle is zoned for single family 5000-9600 square foot lots, effectively class segregating vast swathes to people that can afford a now near-million dollar house, allowing more naturally affordable duplexes, row housing, and apartments on small strips of land alone. Many grandfathered examples still exist, and when they’re torn down they can only become a million dollar single family house. Just 8 unrelated people are allowed to live in one house, no matter how large it is, limiting group rental house affordability. This is what urbanists call “Exclusionary Zoning.”

There’s been a loose ally-ship between white fragility NIMBYs and anti-capitalist growth-skeptics through protection of the century-old built environment, which itself erased thousands of years of indigenous history. Vanishing Seattle, an Instagram account that valuably documents and laments the closure of businesses and replacement of old houses across the city, serves as a nexus between the two ideologically opposed groups. The page does valuable work, not only in historical documentation, but through celebration of POC-owned restaurants that continue to serve their community, and support for projects like the Delridge Food Co-op. However, the photo series draws anger while showcasing (million dollar) single family houses, abandoned malls, office buildings, and even parking lots torn to make way for multifamily homes, including those in historically white-only neighborhoods. Use of hashtags aim to connect all physical change, including new public transportation lines, with insidious gentrification.

Vanishing’scomment section reveals an audience mixture of old Seattle nostalgics also found harassing unhoused people on the “Safe Seattle” Facebook page, and genuine activists that see corporate developers and rising rents, also found on the very different and benevolent “S.A.F.E. in Seattle” Facebook page. The discussions are full of hatred of modern architecture, a praxis increasingly getting picked up by white nationalist vloggersin their attempts to mirror 20th century fascists. The growing dogwhistle Facebook page Architectural Revivalis devoted to bringing back German and Victorian values from a transparently paleoconservative perspective. On the exact same post, half the commenters will complain about how expensive and gentry-looking the project is, and half will complain about how tiny the apartments are and how cheap, generic, and “Soviet” the architecture is. The anger at change is just as strong on posts about genuinely great community-led housing projects. The Africatown Community Land Trust and Capitol Hill Link Transit Oriented Development projects are replacing asphalt lots for hundreds of homes, nearly half low income and rent controlled. Yet they’ve still drawn complaints and claims of gentrification from Vanishing Seattle’saudience due to the buildings blocking a commenter’s property’s view, worry about the kind of people that will live in the building, and distaste for neomodern architecture. Vanishing Seattleis doing important work, but a facilitation to avoid problematically nostalgic attitudes that match “Make America Great Again,” is nowhere to be found.

It’s important to avoid the Capitalist-Libertarian argument that inequality is a result of the regulation itself, and that deregulation will solve everything. Exclusionary zoning formed because the dominant class of property-owning white people had the power to make it happen and the prejudice to want it, while the people it hurt lacked any democratic say. This is exactly the result of capitalism: there can never be democratic policy when there’s inequality, and a class that owns the fruit of other people’s labor. Neighborhoods could be just as segregated through entirely private action, as restrictive covenants were once protected property rights. In Country Club suburban developments today, they absolutely still are.

Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) is the city’s recent policy to increase building height limits in areas “in exchange” for requiring developers build a proportional percentage of the units rent and income controlled for people making 60% or less of the average income, or contribute a similar amount of money to nonprofits that build housing serving people of 0-30% average income. Jon Grant’s primary campaign promise was to increase the demand to 25% of units, with no option for a fee in-lieu of. 25% affordable is a policy that was canned in San Francisco after it shifted nearly all housing development to more profitable hotel construction and ultimately decreased the number of affordable units being built.

After a powerful “Humbows Not Hotels,” movement, the Seattle city council chose to implement MHA in the Chinatown-International District with double the fee that goes towards low income housing of every other MHA area. With the city council hearing the loss of affordable buildings with longtime minority residents, the goal may now be to push development away from the CID. The activist coalition, infuriated by a proposed Marriott Hotel, didn’t see this as enough, and calls for a complete shutdown of construction serving people that make over 30% of Seattle’s average income ($62k), closer to the neighborhood’s average income ($37k), stating, “The CID Coalition is not against development. However, we believe development should not cause the displacement of existing residents and small businesses, and should serve the wellbeing of the community instead of tourists, developers, and the wealthy.” Urbanism must be intersectional and intentionally give space for the voices of people who have been most excluded.

As women of color urbanists, such as Laura Loe, often cite, and white male “broburnists” gloss over, the skepticism of development in the CID and Central District comes from an entirely different place than mobilized opposition against RV parking, houseless shelters, apartments, and duplexes in Magnolia: one of genuine social justice compared to the most traditional NIMBY attitudes. Urbanists don’t always respect this, and often fail to see any need for particular consideration and democratic planning in neighborhoods of high displacement. Those of a low income and people of color have no reason to trust the authorities of city planning. Throughout the history of highways, urban renewal, and housing projects, institutional planning has been used entirely against these groups of people. Compare that to middle class white NIMBY groups: every turn in history has been in their favor. Today they sense a shift from that, feel how awful I-5 traffic is, and have a touch of either disgust or guilt when observing houselessness. To foster equity, urban planners need to work within historically disenfranchised communities, listen, and actively avoid doing the same with neighborhoods and folks that have always gotten their way. Planning cities for the wealthy and without considering externalities was never sustainable.

The most important agreement between socialist YIMBYs and growth-skeptics is that public owned housing is needed, and ultimately the only way to truly provide affordability for everyone. A legacy of 1918-1934’s Red Vienna, the city is a model for YIMBYs. 60% of its housing is public with rent set to under 30% of the resident’s income. Design competitions result in some of the most innovative and diverse architecture in the world. Seattle is known for its incredible parks and greenspace, making up 12% of the total land, priding itself in canopy. With almost exactly the same land area and 2.5 times the population of Seattle, 51% of Vienna is greenspace, and none of it is single family zoning. All with a skyline less towering than Bellevue. It’s essential to note that population density is directly aligned to climate footprint: Vienna generates just three metric tons of CO2 per person, compared to Seattle’s five, and the US average of 17.

Zoning applies as much to public, non-profit, and community owned projects as it does to profitable private development. High Point’s mixture of Seattle Housing Authority and privately-owned triplexes look practically suburban, but they would be illegally dense to build on the other side the “Low Rise 3” zoning line. The coming Africatown Community Land Trust and Capitol Hill Link projects with 40% low income units both build to their midrise limits of density in the same way entirely market-rate construction would. It would never be feasible or most beneficial to have public housing of luxurious $1 million 5000sqft single family lots.

It’s reasonable that some leftists see upzoning as a neoliberal deregulation. To validate their concerns, folks like Roger Valdez (Smart Growth Seattle) argue against any form of housing regulation. They hold the capitalistic perspective that the mass-producing competitive free market would make housing affordable, just like any consumer product. However, most urbanists in Seattle are socialistic and see upzoning as a trade from regulation that currently promotes McMansions and enriches the few homeowners to one promoting modest and affordable homes.

As much as up-zoning is often seen as an evil present to developers, it can be the intentional policy decision to reverse a framework of exclusionary zoning. The case fought so heavily by Seattle Displacement Coalition already has good examples: A former gas station going through toxic waste cleanup at 4700 Brooklyn was set for the construction of a six-story, 74-unit apartment building. After Mandatory Housing Affordability and a rezone from 65’ to 240’ was applied to the U-District, the plan was revised to a 24-story, 247 apartment tower, contributing $3.2 millionto low income housing and service non-profits like LIHI. The site is one block walk away from the Brooklyn subway station opening in 2021. What was a sea of asphalt and noxious fumes will soon be a sustainable home for hundreds of students that will frequent the local shops of the U District. Pre-upzoning, buildings across the U-District were still being replaced to the generic six story height limit. Now, the replacement of one lot can house the same number of people that replacing three to four lots did just a year ago. This will mean less visually impactful growth than if the city had kept the six story height limits that rapidly homogenized New Ballard, greater diversity of architecture, and more sustainable of homes.

From the late 1800s and through the 1980s, Single Resident Occupancy hotels provided incredibly affordable housing in Seattle and other cities with small private rooms and common bathrooms and kitchens. These often served as dorms for adults on the edge of houselessness. Almost all of these buildings were systematically demolished in Downtown’s series of urban renewals: fire regulations, 1970s parking garages and freeways, 1980s convention centers, and the 1990s tech, hotel and shopping district booms. The city did not consider residential hotels housing while measuring the displacement impacts of their plans. This kind of low income, adult-dorm had a brief resurgence in 2013 as “apodments,” but was quickly banned after neighborhood groups expressed concern over parking and claimed the rooms were inhumanely small.

As recently as 1980, houselessness was practically non-existent. Rev. Rick Reynolds of Operation Nightwatch noted, “[In 1980] there was a single woman sleeping in the Public Safety [building] lobby. She was notorious in Seattle. She was almost newsworthy. There was a public effort to get this one woman an apartment.” That era ended during Reagan’s neoliberalization that included the defunding of mental healthcare and public housing. “All of a sudden a trickle became a flood–20 years later we’ve come to accept homelessness as a given.” From 1960-2000, 20,000 units of low income housing in downtown Seattle were lost, 36% of the buildings going to build parking garages for suburban commuters. As houselessness rose in the 1990s and got in the way of their new shopping district, the city passed various ordinances to criminalize bodily functions, sitting, and sleeping, while cancelling plans for a hygiene center with public washrooms. In the 2001 Real Change article, “A Prologue to Homelessness,”Trevor Griffey concludes:

This is no coincidence. These two disparate events–the rise in homelessness in Seattle and downtown’s transformation and economic “revitalization”–are directly connected. To build a downtown dominated by upscale retail shops and tourist spots, expensive hotels and restaurants, high-rise office towers, condos and parking lots, developers first had to tear down or convert the historic buildings already there. And those buildings, largely residential hotels and apartments with retail first floors from the turn of the century, provided the majority of the region’s very low-income housing. Once that housing was gone, downtown developers were free to build skyscrapers and freeways, convention centers and parking lots, while those who had once depended on this housing of last resort were now, literally, left out in the cold.

Commercial avenues, such as Broadway, ‘The Ave,’ California Junction, and Ballard’s Market Street, host the collective identity of neighborhood that has remained so culturally crucial over a century since they were pre-annexation downtowns. Seattleites in all neighborhoods derive community from the sidewalk they can stroll into loved ones on. In the 1990s, the city knew population and job growth was coming. It devised a plan of Urban Villages–a sort of compromise with single family neighborhood groups. Neighborhood councils tasked with zoning allowed mid-rise mixed-use development along existing commercial drives, while just a block perpendicular the number of families allowed in the craftsman grid was and is protected at fewer than what actually exists. In cases like Greenwood, the areas that allow any form of multifamily housing shrunk from the urban village process, meaning a triplex legal in the ‘90s could only be replaced by a house today. Limiting growth to these very narrow wedges has meant the very visible rapid replacement of the public establishments we all seek and share memories of. It’s meant the replacement of a diverse built environment with an era of design controlled by Seattle’s Design Review Process that approves a certain look and halts anything else, leaving lots empty for months of debate.

Prior to the 1990s urban village plan, Greenwood allowed multi-family homes a gridded walking distance from the bus – now it’s a skinny line

Whether involved politically in housing or not, disgust and comments of gentrification at construction of any kind is a predominant topic of small talk in Seattle. New apartments that both market themselves as luxury and are ridiculed for being luxury are often studios of 200sqft lacking bathtubs and even stovetop ranges. They’re expensive because half as many homes are built as the population is growing, and landlords will always take the highest bidder, most often this being a tech worker. The displacement that’s often ignored is from single family neighborhoods without any policy change. In areas of relatively low property values, 1940s era houses often sell for surprisingly cheap, and are quickly replaced with McMansions that bring million dollar houses to a neighborhood for the first time, or $1.4m houses to a place with more valuable land. Last year, Mike Rosenberg of the Seattle Times pointed out, “Across King County, the average demolished home is a 1,300-square-foot, single-story structure built more than 70 years ago, with a small yard. The replacement house is typically more than twice as large—3,000 square feet and two or three stories.” Current zoning encourages modest houses to become luxury ones serving no greater number of people. Lower income ownership is lost by allowing only one type of home to be built. In other cases that make Vanishing Seattlereaders equally mad, single family houses in the few multifamily areas are replaced with row houses. Despite both looking like and being dubbed “luxury housing” in a way older craftsman houses are not; new higher density construction is legitimately more affordable.

Almost universally, even brand new attached houses sell for significantly less than older detached houses at an average of 42% cheaper. Brand new town and rowhouses are also physically more akin to historic Seattle houses in their modesty than the kind of single family houses the city requires to be built today, both generally around 1,500sqft with 3 bedrooms and 1-2 bathrooms. They make a lot more sense than the upward trend in house size inverse to the downward trend in family size. Furthermore, construction of the rowhouses that Vanishing Seattle loves to hate saves more of the character craftsman homes from demolishment to make way for McMansions:

Some highly desirable neighborhoods with little multi-family zoning are at greatest threat of having old single-family homes torn down for builders to replace with newer, bigger, and fancier single-family homes. We can catch a glimpse of this trend in neighborhoods like Ravenna and Sunset Hill which are almost entirely covered in single-family zones and saw some of the most new single-family home construction last year. The new single-family homes in both of these neighborhoods sold for an average price of $1.4 million last year. Every townhouse and skinny not built increases competition for existing single-family houses, and the new single-families push up home prices without adding supply. That upward pressure on prices, spread across the city’s 133,000 single-family lots, pushes more small, old homes across the threshold from “leave alone” to “tear down and replace”: the higher prices, the more McMansions get built.

This recent meme on gentrification sums up the concocted association between architecture and affordability. The building pictured is a public low-income senior home built by Seattle Housing Authority and operated by Providence Health & Services. Aesthetic quality has absolutely nothing to do with the morality of a project, and trying to stop housing out of personal taste will only further in-affordability and displacement, killing lower income neighbors. Yet it’s completely understandable that in an era of displacement, the physical design character of construction will become associated with the social evils of gentrification.

This recent meme on gentrification sums up the concocted association between architecture and affordability. The building pictured is a public low-income senior home built by Seattle Housing Authority and operated by Providence Health & Services. Aesthetic quality has absolutely nothing to do with the morality of a project, and trying to stop housing out of personal taste will only further in-affordability and displacement, killing lower income neighbors. Yet it’s completely understandable that in an era of displacement, the physical design character of construction will become associated with the social evils of gentrification.

It’s also important to understand every old house in Seattle isn’t an architectural masterpiece of historical significance.Most west coast craftsman bungalows, developed in the “Streetcar Suburb” era, are one of several Sears catalog models, delivered with parts and instructions similar to IKEA furniture. It’s the century of being used and maintained as homes that so often has given two identical adjacent houses unique character, something houses built today will gain with time. Old houses certainly aren’t better ‘built to last’ than what modern health, fire, accessibility, and energy efficiency standards bring.

The most affordable rental housing in Seattle remains group houses, at often around $500 per person, but from anecdote, they’re disappearing. Many landlords seem to sense a height of the market and are cashing out on their properties: I’ve got two friends from group houses of 8 people with 20+ years of history facing this. While both cases are tragic, the density and kind of people that will come of this are different in each case due to respective zoning. One will become apartments and commercial, likely home for more people than before – and if MHA comes to the neighborhood soon enough, it’ll include or fund low income units. The other house will be remodeled or replaced and sold to a small single family for $1 million, clearly causing greater displacement. At November 1st’s city council hearing, one woman described regaining housing on four separate occasions, each lease ending with the landlord renovating to increase rent, evicting her family to shelters.

In July 2015, the city’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda included 65 recommendations to guide policies. One stood out to The Seattle Times Editorial Board: the blanket replacement of single family zoning with low rise residential. This would resume construction of duplexes, triplexes, flats, and small lots in the 65% of the city that has banished them for half a century. Immediately after a scathing editorial, Mayor Ed Murray backed down on touching single family houses, promising that in the following year they’d only push for more backyard cottages and upzones in existing multifamily areas.

In 2016, Queen Anne’s Community Council, a classical NIMBY group, sued to stop the city from lowering permit requirements on backyard cottages and basement apartments. Using laws intended to protect the environment, the group is trying to keep requiring parking spots on-site that limit the number of houses eligible. Density is of course essential to sustainable living: New York City has the lowest per capita footprint of any place in the US, and preventing infill in Seattle means stealing even more indigenous land to pave over ecosystems for sprawl. The group only needs to pretend to care about the environment to keep poorer people out of their neighbor’s backyard. Accessory suites allow for neighborhoods to become a mixture of wealthier homeowners and lower income renters, adding a lot of density with minimal physical change of character. Magnolia’s neighborhood group has used similar means to stop low income housing from being built on (presently fenced parking lot) surplus Fort Lawton military property, and other efforts are underway by Wallingford Community Council, the group responsible for the ominous, “Keep Seattle Livable!” signs.

As all the “missing middle” options of bringing affordability have been curtailed, the city continues to concentrate development in the narrow urban villages, frustrating everyone.

Parking remains a primary concern of households, so their logic targeted the frequent bus lines along each avenue that can support apartment dwellers. In their pleas to preserve the current border and parking requirements, Wallingford Community Council argues one block perpendicular to that line somehow needs to be car-dependent.

Current zoning in the city accelerates the crisis, certainly helping private interests, as well as accelerating climate change, by having the market replace modest homes with McMansions instead of more modest homes. This doesn’t mean the city should or can rely on market-based solutions to solve the housing crisis. Zoning applies equally to what the city and nonprofits can build, and what a post-socialist revolution built environment would have to deal with. Stable and safe deeply affordable housing will never be profitable enough to be provided by capitalist institutions again, but that’s not a reason the city should subsidize capitalism’s externalities by only providing public housing to the poor. If the city were to purchase multi-family buildings, rents could be stable at a place to pay the mortgage and maintain the building, rather than fluctuate with the housing market. With a level of public ownership similar to Vienna’s, it’s likely the private market too would stabilize. Public housing in Seattle cannot, however, look like three person families occupying land with 3500sqft houses with 3 car garages.

The uneasy shared zoning aims of some leftists and genuine NIMBYs may soon break down. Housing For Allis a new coalition and campaign that includes the Transit Riders Union, Democratic Socialists, Housing Now, Standing Against Foreclosures and Evictions, Socialist Alternative, Neighborhood Action Coalition, Stop the Sweeps, The Urbanist, SHARE, and Camp Second Chance, a mix of leftists that include both growth-skeptics and urbanists, and a lot of folks doing hard work to improve equity.

The goal of the coalition:

- Quadruple the number of zero-$20k income (30% AMI) units the city will build over the next decade.

- Change zoning to allow a variety of affordable home types in every neighborhood – pointing out SROs (“apodments”), backyard cottages, and basement apartments

- Improve the process for obtaining housing assistance

- Stop the sweeps that cyclically displace people and seize their possessions. Implement last year’s ACLU bill that defines suitable sites for encampments and provide them with sanitation services when there aren’t the resources to house people. Immediately defund the city process for 2018.

- Stop putting people living in vehicles in debt with tickets and towing.

This platform is nuanced, supported by people that have spent the better part of two years bickering, and includes the exact measures needed to solve houselessness in Seattle. The groups primarily fighting against north Seattle upzoning under a guise of social justice, like Seattle Displacement Coalition and Seattle Fair Growth, are nowhere to be found. 24,000 new low-income homes requires increased density and zoning capacity.Housing for Allis successfully packing city hall to represent the folks that don’t traditionally have the time or energy to make public comment. The proposal for a business head tax to house people may have failed, but multiple ‘no’ votes made promises that Housing for Allcan hold them accountable to. González said if there isn’t a head tax by March, her own proposal will generatedouble the fundsof the Herbold, O’Brien, Sawant, Harris-Talley bill.

As divided as housing justice can be, there’s absolutely a hope in Seattle for meaningful progress. Understanding the “never great” history of the city is essential. Only with it can we understand malicious trends like exclusionary neighborhood groups reappearing, even when modern incarnations use token words of justice. Aesthetic preferences in architecture deserve little space in the life or death question of housing availability, and nostalgia for a classical built environment is problematic. With an ongoing coalition, we can stop displacement and the sweeps. As Federal public housing is recklessly dismantled, we can demand better at a local level. A necessary step isreforming our unjust tax systemto something more progressive. It will be a long fight, but the actionable policy to reach housing as an entitlement will develop the city more sustainably and equitably than ever before. “Housing is a human right” cannot be treated as just a metaphor anymore.